Jamesport man, a retired FDNY firefighter, battles 9/11-related cancer

On the night of Sept. 10, 2001, Steve Brickman helped his friend Bill Roberts build a deck at his home. When they finished, Mr. Roberts headed to work as a New York City fireman with Ladder 113 and Mr. Brickman spent the night. Early the next day, a clear, bright morning, Mr. Brickman returned to his Sag Harbor home. Just over a year had passed since Mr. Brickman was forced into early retirement as a city fireman — the wounds from fighting countless fires on the front lines had taken their toll — and he filled the time as best he could with handy work.

He fell back to sleep while his wife, Colleen, got ready for work. She rarely turned on the television in the morning, but happened to have it on in the background when the news flashed: American Airlines Flight 11, bound for Los Angeles, had just crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center. She couldn’t comprehend exactly what was happening. She woke up her husband, who immediately began to think of all his former colleagues — his brothers — who were about to put their lives in danger.

The terrorist attacks that unfolded and the subsequent collapse of both towers killed nearly 3,000 people, including 343 members of the FDNY. As Mr. Brickman watched the chaos from afar, he was faced with a decision. In his heart, he knew he needed to join the rescue efforts. His wife, fearing the unknown of what could still happen, wished for him to remain home, to stay safe. But she also knew that was unlikely.

“I knew that he was going to go in because that’s what he’d do,” Ms. Brickman said. “He had to be with the people that were affected.”

About 30 hours after the attack, Mr. Brickman arrived in downtown Manhattan to join his former colleagues with Engine 58. For nearly two weeks, often with little sleep, he assisted in bucket brigades and would cram firefighters into his pickup truck to drive them back and forth to the firehouse after their six-hour shifts.

More than a decade after 9/11, Mr. Brickman’s decision to voluntarily join the rescue efforts resulted in a steep consequence. In 2013, he was diagnosed with Stage 4 head and neck cancer and Stage 4 lung cancer. Doctors attribute the diseases to the toxins he inhaled at ground zero.

•

Mr. Brickman’s fascination with firefighting started at a young age. An uncle, John Kopp, started on the job in 1962, the same year Mr. Brickman, now 54, was born. His uncle would tell stories about the job and, while other kids would drift off, he would listen intently. As he grew into his teens, living in Flushing, Queens, he wasn’t a great student and would often find himself in trouble. Joining the fire department gave him a purpose.

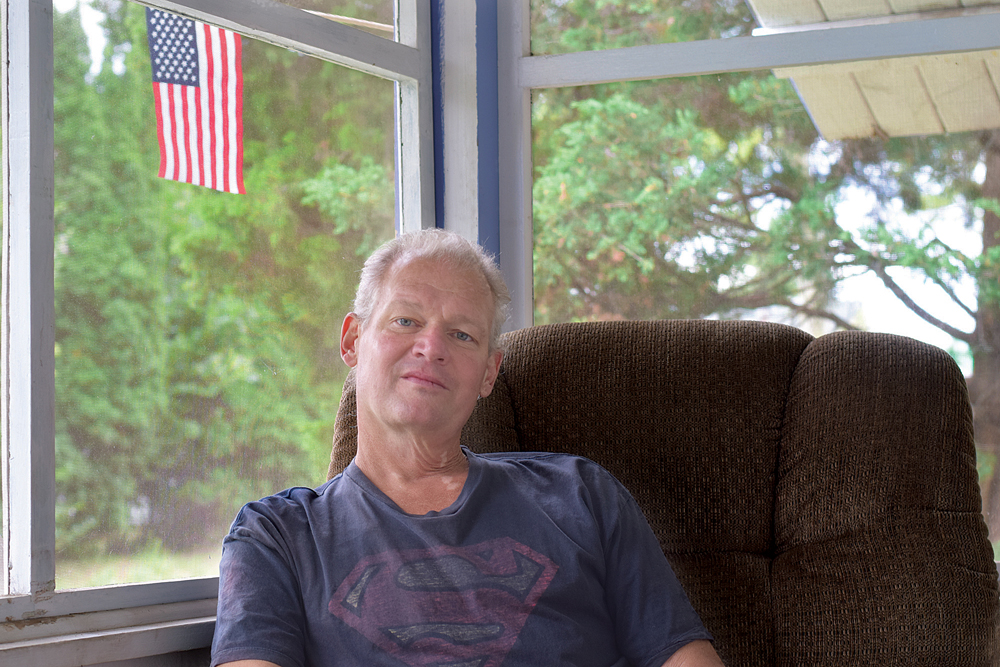

At 23, he officially became a member of the FDNY, joining Engine Company 58/Ladder Company 26 in a busy section of East Harlem. The job perfectly suited an adrenaline junkie like Mr. Brickman, he recalled this week in an interview at his Jamesport home, where’s he lived with his wife and two sons since shortly after 9/11.

With the engine company, Mr. Brickman’s job was to put out the fire. Like an athlete who wants the ball in his hands at the crucial moment, Mr. Brickman always wanted to be the fireman on the nozzle.

“You want to be the guy that gets that goal or throws that last pitch,” he said. “Some people are on the job for different reasons than I was. I was there to fight fires.”

It wasn’t a position that came with the glory of pulling victims from harm’s way, but he loved every minute of the job and the camaraderie that formed in his firehouse. He loved to be in the thick of a blaze.

He was trained to be an aggressive firefighter, and in New York City fires are rarely ever fought from the outside. That meant getting inside, oftentimes in unsafe vacant buildings that could have any number of homeless people or squatters inside. The dangers were evident.

In 1990, a ceiling collapsed on Mr. Brickman and embers from the fire caused third-degree burns on his left knee. He missed 8 1/2 months of work. In 1999, he became trapped in an apartment while fighting a fire and ran low on oxygen. He was rescued through a window after firefighters cleared branches to make room. He suffered additional burns, one of which required a skin graft on top of a previous skin graft, a rare procedure at the time that ultimately led to his retirement after only 15 years.

“I’d probably still be on the job if I was fortunate enough to still be alive,” he said.

•

In January 2013, Mr. Brickman visited an ear, nose and throat specialist after dealing with swallowing issues. Several visits to a dentist the previous summer hadn’t revealed anything. He eventually discovered what felt like an Easter egg behind his left ear. A biopsy revealed the Brickmans’ worst fears.

A PET scan a few days later uncovered more bad news: Mr. Brickman also had lung cancer, typically found in smokers.

Mr. Brickman told the doctors his parents had smoked when he was a kid and he had been a city fireman for 15 years. Those weren’t the culprit, they said. Then he described his time at ground zero.

“They said, ‘That’s it. We’re finding all these weird cancers 10 years and 11 years out,’” he said.

He quickly got into Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, where his oncologist discussed his initial diagnosis with a team of specialists on a conference call to determine the best treatment.

“My oncologist said to me, ‘Steven, you’re stumping the great minds of Sloan Kettering,’” he recalled. “I said, ‘Doc, that’s not why I came here. You guys are going to fix me.’ And so far, with Stage 4 lung cancer, most guys don’t live long.”

From the earliest moments when he discovered he had cancer, Mr. Brickman cautioned doctors never to give him a life expectancy. He didn’t want to hear he had six months or a year to live. He planned to fight the disease as best he could, keep up his faith and hope for the best.

He’s undergone a barrage of treatments since his initial diagnosis, from radiation and chemotherapy to a new drug that’s part of a clinical trial designed to specifically target his symptoms. He had always been a fit, strong man and once weighed as much as 240 pounds, he said.

At one point, when his oncologist encouraged him to have a feeding tube during his treatment to keep his weight up, he fought against it. He didn’t want to deal with the added risks and told the doctor he could afford to lose a few pounds.

“You have to advocate for yourself,” he said. “I’m pretty in tune with my body, so I said no.”

The decision appeared to pay off.

After his head and neck chemotherapy and radiation in February and March 2013, Mr. Brickman was informed that part of his left lung would be removed that June. The cisplatin drug used in the initial chemotherapy had also shrunk part of the lung tumor. The surgeon removed the upper lobe of his lung, a surgery that, because the tumor had shrunk, could be done laparoscopically with several small puncture wounds rather than a large incision.

“It was really phenomenal,” he said. “Two days later I walked seven blocks in 100-degree weather and took the Hampton Jitney home.”

Mr. Brickman said he typically feels well, even as the dangers persist. Doctors found three lesions remaining on his lungs that started to grow, which prompted his current treatment plan. The hardest part is the unknown, when any scan he routinely receives every two months could mark the beginning of the end.

“Those regular visits are like, God … here we go again,” he said. “ ‘What are they going to say today?’ ”

His most recent scan came back clean last week, providing a welcome sigh of relief until the inevitable next moment of truth.

•

Two years before Mr. Brickman’s initial cancer diagnosis, President Obama signed the James L. Zadroga 9/11 Health & Compensation Act, which was named after a New York City Police Department officer who died of a respiratory disease related to his efforts after 9/11. The fund was designed to help the growing number of first responders who were succumbing to various diseases in the years following the terrorist attack.

The Zadroga Act was first written to cover 9/11-related health problems only through 2015. When efforts stalled in Congress to extend the health care program, it took a long, consistent effort by the families of those affected to get the government to act. Jon Stewart, former host of “The Daily Show,” was a strong advocate for first responders and produced a powerful segment last December in which he attempted to reinterview first responders he had originally met 5 1/2 years earlier. Only one of the four men could return. One had died and the other two were too sick to return.

The Zadroga Act was first written to cover 9/11-related health problems only through 2015. When efforts stalled in Congress to extend the health care program, it took a long, consistent effort by the families of those affected to get the government to act. Jon Stewart, former host of “The Daily Show,” was a strong advocate for first responders and produced a powerful segment last December in which he attempted to reinterview first responders he had originally met 5 1/2 years earlier. Only one of the four men could return. One had died and the other two were too sick to return.

Later that month, the House and Senate both voted to extend the Zadroga Act for 75 years, guaranteeing that men like Mr. Brickman will continue to receive the coverage they need.

“Isn’t that what this country is about?” Mr. Brickman said. “You take care of your own.”

Mr. Brickman, who said first responders weren’t provided adequate protection from the toxic air at ground zero, tries to avoid getting swept up in the politics. He knows there have been some local politicians who fought hard for the first responders. And he knows that without the support of the health coverage, he could never afford medications like one drug, used as part of a study, that cost about $13,000 a month.

“It just seems unfair that they would stretch this out and give people like me anxiety,” he said.

•

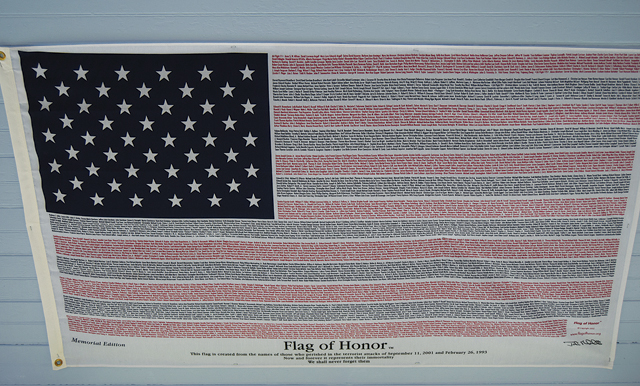

Mr. Brickman rarely talks about his experiences on 9/11 or attends support groups, although he recently visited Fighting Chance in Sag Harbor, a group for cancer survivors. He shies away from attending local 9/11 memorial ceremonies as an honored guest and he has never visited the ground zero memorial. On a recent visit he wore a shirt with the Superman logo on it and Superman-themed shoes. His kids, Steven, 13, and Quinn, 10, like to think of their dad as a superhero after everything he’s been through. He sits on the porch of his Jamesport cottage beneath a large banner of a U.S. flag designed with the names of all the 9/11 victims.

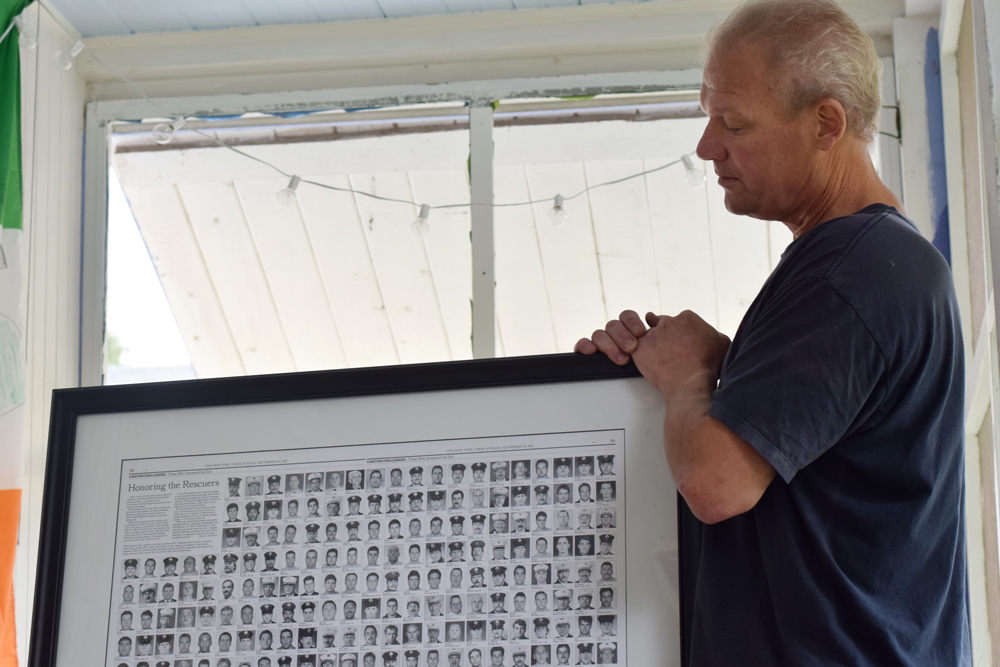

He has a large framed copy of a 2001 issue of The New York Times that features the photographs of every firefighter who died on 9/11, such as Lt. Robert Nagel, with whom Mr. Brickman worked closely at Engine 58. He doesn’t display the frame; his house is too small, he said. But he occasionally takes it out to show his boys and share stories about the firefighters he knew. His son Steven’s middle name is Robert after Mr. Nagel.

Steven Jr. was born two years after 9/11. Mr. Brickman said his son helped provide him with a renewed sense of life after the depression that came with leaving his job before he was prepared to and the devastation of 9/11. The former fireman became a stay-at-home dad while his wife worked as a waitress.

“He was in charge of everything,” Ms. Brickman said. “He was always very hands-on with the kids.”

Ms. Brickman typically stayed behind with the kids when her husband traveled into the city for doctor appointments. He relied on the steady support of friends and family, such as Fran Trapani, a retired fireman in a neighboring firehouse, his brother Gerard, who’s also a fireman, and a lifelong friend, Chief John Sudnik. Mr. Brickman and Mr. Trapani became close friends. Mr. Trapani’s mother had died at Sloan Kettering and two of his brothers have undergone cancer treatment.

Mr. Trapani, who lives in Farmingville, was familiar with the facilities in the hospital and agreed to help guide his friend.

“He was there for every single visit,” Mr. Brickman said. “He’s a great guy. I don’t know how I would have done it without him.”

As Mr. Brickman looks back now, 15 years after 9/11, there are no heroic stories of how he helped pull someone from the rubble. Hope quickly faded at ground zero of finding anyone alive after a few days. The destruction was simply so catastrophic that even finding bodies intact was rare. He remembers the blank, empty stares on the faces of firefighters; the small fires that burned untouched around ground zero as people dug through debris; the late summer heat; the smell of death that set in as time passed.

“It was the kind of s— that made me cry when I called my wife,” he said.

It would be understandable for Mr. Brickman to wish he had never left his home that September. He had no professional duty to be there. They never did pull anyone to safety. And he’s now stricken with diseases that could end his life.

But he doesn’t look at it that way.

No regrets, he said. He still dreams about putting on the uniform.

“If I could fight one more fire I’d be thrilled,” he said.