Special Report: ‘Dark days’ at the Cutchogue labor camp

Ask around about the former labor camp on Cox Lane in Cutchogue and the reaction you’ll get is often the same: a slight frown, a widening of the eyes or a small shake of the head. The history of the camp — which housed hundreds of migrants during its heyday in the 1950s and ’60s — is now seen as an embarrassment, longtime farmers and local residents say.

“It was horrible conditions,” said Josephine Watkins-Johnson of Greenport, who knew many who worked the fields at the time. “That was the worst camp of any of them.”

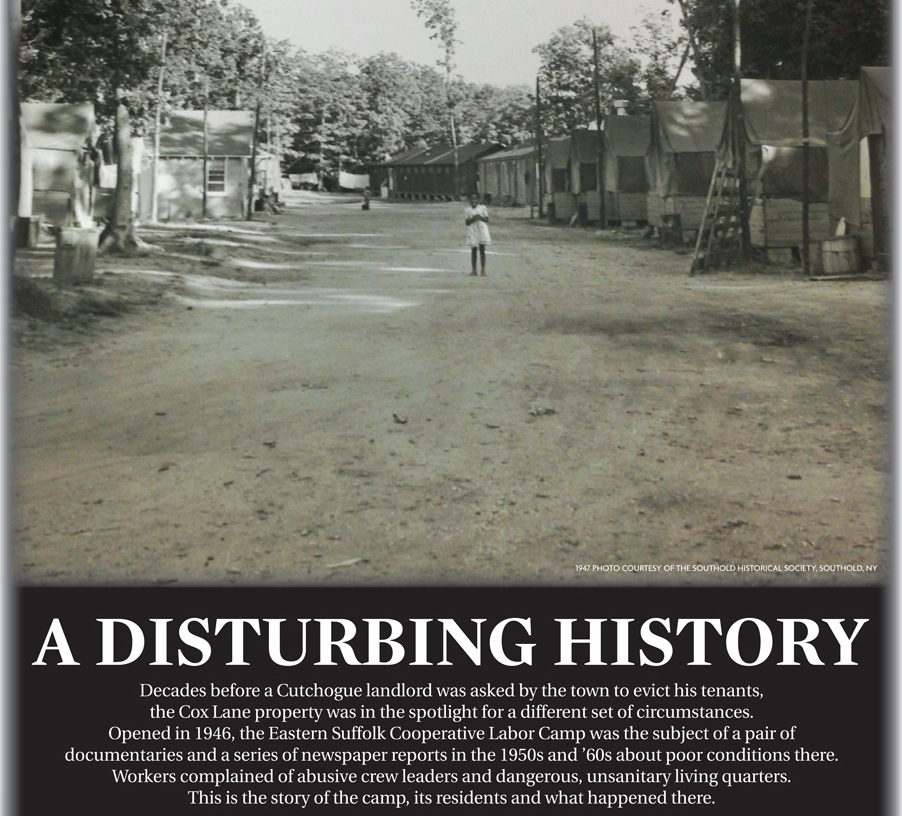

The Cutchogue migrant camp, which included barracks-style housing for single men and families, opened in 1946. It was the last of three camps that had been created in Southold and Greenport during World War II to help farmers tend their fields.

The Eastern Suffolk Cooperative, a group of 139 Southold Town and Shelter Island farmers, spent $15,000 to build the camp, which it operated along with the Suffolk Farm Bureau, according to a 1946 article in the Long Island Traveler.

It would become one of more than 50 camps — though many were much smaller — scattered across Riverhead and Southold towns, according to a map created by Suffolk County health officials in 1959. More than 1,000 migrants were working on the North Fork at that time, the map’s legend states.

But throughout the 1960s, migrants who flocked to Long Island each growing season to work the fields complained about subpar conditions at the Cutchogue camp.

It was criticized as messy and dangerous, a place that barely met county building codes as its owners cut corners on maintenance and supervision. Abusive crew leaders took cuts from each migrant worker’s pay and allegedly manipulated the workers to keep them in poverty and debt, according to contemporary New York Times reports.

Only after years of exposés by television and newspaper reporters, as well as investigations by federal and county government agencies, were issues at the camp finally addressed.

Prime Purveyors purchases former labor camp

Though the Eastern Suffolk Cooperative sold the camp in 1983 to Prime Purveyors, which built a dry goods warehouse on the property soon after, it’s unclear exactly when the camp closed for good, as documentation about the its final days is scarce.

Today, the former camp property is at the center of a dispute between Prime Purveyors owner Robert Hamilton and Southold Town, which is accusing him of violating town code by renting out apartments at the site.

Still, for the those who remember it, the former labor camp remains a shameful and rarely discussed part of the North Fork’s farming history.

“We grew up and didn’t think anything was wrong,” said Long Island Farm Bureau executive director Joseph Gergela, whose family ran a Jamesport potato farm when he was young. “Those were part of the dark days.

“We were kids,” he continued. “Now, I look back and say, ‘Oh my god.’ We all look back and remember these things and are shaking our heads that this was the way it was.”

That feeling is echoed by some of the farmers who worked on the North Fork during the years the camp was open.

Cutchogue farmer John Zuhoski would pick up migrant workers at the labor camp each morning at 7 a.m., said his wife of 65 years, Lucille.

The workers came each morning, she said, prepared with a breakfast egg sandwich provided by the crew leader. At the end of the week, that breakfast would be the first of many deductions from their salaries, part of a cycle of endless debt.

Ms. Zuhoski told The Suffolk Times she can remember her nine children going to the Dixie Inn, the combined restaurant and convenience store at the labor camp, to buy soda, ice cream and candy.

The Zuhoskis did what they could to help the workers on their farm.

Ms. Zuhoski struck up a friendship with one of the mothers who lived temporarily at the camp. After the migrant family moved into a nearby house, Ms. Zuhoski would take the black couple’s three children to Catholic Mass every Sunday.

They were all baptized in the church, with Ms. Zuhoski as their godmother.

The Zuhoskis said farmers at the time knew little about camp conditions or details of the alleged abuses there — only rumors. One pervasive story was that the crew leader would beat migrants who stepped out of line.

“He was awfully mean,” Mr. Zuhoski said. “He treated his help bad.”

But at the time, his wife said, the farmers had other concerns. They had farms to run, cauliflower to pick, fruit auctions to manage.

“We didn’t think much of it,” she admitted. “We needed help and they were right there … It wasn’t really a thought.”

Henry Domaleski, now in his mid-80s, employed some migrant workers from the camp on his Cutchogue farm at the time.

He said he knew the crew leader was harsh but didn’t know the full extent of what was going on until after the camp closed.

“They were like slaves,” Mr. Domaleski said. “Sometimes the head guy who was the crew leader, he would beat the s— out of them.”

It was only after documentaries and media attention revealed conditions at the camp that farmers took the situation seriously, Ms. Zuhoski said.

Some, like Mr. Domaleski, believe there was nothing that could have been done. He said he doesn’t have regrets about the situation. The farmers, he noted, were in a tight spot, too.

Mr. Domaleski said farmers weren’t making enough money to raise salaries at the time and that there were no wage protections that would have forced farmers to pay their help more.

The farmers really just needed cheap labor, he said, and the crew leader at the Cutchogue camp provided it in abundance.

“The co-op had to make a deal with that guy [the crew leader],” Mr. Domaleski said. “There were no labor laws then. The [farmers] paid what the hell they wanted to pay.”

The Zuhoskis said they would have spoken up had they fully understood what was going on at the camp at the time.

“I’m sure most of the farmers would have said something,” Ms. Zuhoski said. “I can’t imagine a bunch of people living like that.”

MEDIA EXPOSURE

Local reaction to the predominantly black migrant workers who lived at the Cutchogue labor camp was mixed from the start.

They were, depending on who you asked, “America’s most irresponsible, most hard-working, most improvident, most victimized, most destructive, most exploited, most unresponsive, most disenfranchised citizens,” Ruth Schier wrote at the start of a series on migrant workers that ran in the Long Island Traveler Watchman in May 1956.

The atmosphere wasn’t improved when accusations surfaced beginning in the 1950s of poor conditions and abuse at the camp. The NAACP condemned the migrant housing in a media blitz in 1957.

Then-governor Averill Harriman ordered an advisory council to investigate, but a year later the group declared the Cutchogue camp the “best we’ve ever seen,” according to a 1958 Newsday article.

Still, the complaints continued, soon reaching a national stage. For his groundbreaking 1960 documentary “Harvest of Shame,” Edward R. Murrow shot several brief scenes at the Cox Lane camp.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Newsday wrote two investigative series about the camp, alleging that those operating the camp didn’t do enough to provide sanitary and safe living conditions for the residents.

Migrant workers themselves also called the conditions deplorable. Eddie Clark, a migrant worker who stayed at the camp in 1964, called the place a “hellhole” in an interview for the 1996 book “Heaven and Earth: The Last Farmers of the North Fork” by Steve Wick, a Cutchogue resident and an editor at Newsday.

“[It was] a bunch of shabby cabins up next to each other,” he told Mr. Wick.

Meanwhile, local clergymen Ben Burns and Arthur Bryant campaigned for help at the camp. Eventually they succeeded in having workers from the Volunteers in Service to America program sent to the camp to help the impoverished migrants deal with medical care and buying groceries.

Suffolk County began cracking down on the camp and at one point advised that it be completely shut down and rebuilt from scratch. Farmers attempted to get federal aid to repair the camp, but were rejected.

The camp was still standing and in operation in 1967, when a news team descended on Cox Lane.

The documentary “What Harvest for the Reaper?” emerged from that visit. The film tracked the plight of the migrant workers, following crew leader Andrew Anderson as he berated his workers and forced them into debt. The farmers interviewed for the documentary said the migrant workers were to blame for the poor conditions.

“I think it’s very unfair for us as board members to be nursemaids to those people,” one board member of the farmers’ cooperative says in the film. “They wish to live in filth, not wash and go to the bathroom in their own living quarters. There’s no way I can stop it if I’m home in my own clean, lily-white sheets, which I change weekly.”

Soon after the documentary aired, public pressure against the camp mounted. In June 1969, the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Migratory Labor held a two-day hearing to discuss working conditions at the camp. News articles, the Rev. Bryant and the documentary were all used as sources in the proceedings.

In 1970, the Suffolk County health department declared the camp “unfit for human habitation,” according to a Traveler article. The health department ordered it closed, evicting the 24 people then living there, though news reports indicate the camp was back up and running later that year.

Joe Gergela, now executive director of the Long Island Farm Bureau, said the government imposed strict regulations that shuttered many of the labor camps dotting Long Island.

“We wanted to make sure that there could be no abuse and that people were treated right and fairly,” he said.

DEATH, VIOLENCE AT THE CAMP

One of the most jarring incidents in the Cutchogue migrant camp’s history was the fire that swept through a barracks on the property, killing three workers trapped inside and a fourth who escaped but later succumbed to his injuries.

At about 7 a.m. on Oct. 8, 1961, a “kerosene space heater-type stove, forbidden by law in labor camp buildings,” exploded in one of the wooden buildings that housed the migrant workers, according to a story in the Riverhead News-Review.

All but three of the 20 workers living in the building made it to safety, the article states. The victims who burned to death were Roy McCoy, a 23-year-old from North Carolina; 42-year-old Charles Jordan from Ohio; and 41-year-old James Davis of Baltimore, Md.

A fourth man, 23-year-old James Overstreet of Louisville, Miss., fled the burning building with “third-degree burns covering most of his body,” according to the story. He later died at Eastern Long Island Hospital in Greenport.

The blaze was extinguished by more than 100 volunteers from the Cutchogue and Mattituck fire departments, who were unable to save the building, which was destroyed.

All told, $25,000 worth of property — including the possessions of the migrants — was destroyed.

Camp manager John Murphy said at the time that workers had brought the illegal stoves into the camp themselves. Assistant district attorney Ted Jaffe said there was “probably no criminal liability against the camp owners” at the time of the fire, but railed against the “disgraceful conditions” in the camp of about 200 migrants.

“There is an air of general sloppiness about the place,” he told the News-Review at the time.

The fire was the biggest disaster to occur at the farm, but it certainly wasn’t the only time emergency responders were called to the property. Over the years, several people were injured during fights in the barracks, according to contemporary news sources.

A 2011 biography, “Preachin’ the Blues,” claims that blues guitarist and singer Eddie “Son” House was arrested while working at the labor camp in October 1955 after stabbing and killing a man who was allegedly trying to rob him. Mr. House was released after a Suffolk County grand jury did not indict him on manslaughter charges, “apparently accepting House’s argument of self-defence,” author Daniel Beaumont wrote.

Another well-known incident during the camp’s later years involved the discovery of a cache of weapons and ammo, as well as Black Panther literature. On July 19, 1972, four Long Island Farm Workers Service Center volunteers were arrested on felony reckless endangerment charges after migrants at the camp reported hearing gunfire, according to an article in The New York Times.

The three men and a teenage girl said they were “just having target practice” and weren’t members of the Black Panthers, according to the article. One of the men told the Times that he was selling the literature and buttons because he would get 10 percent of the profits.

SCHOOLING AT THE CAMP

The Cutchogue labor camp opened a small school for migrant children in 1949, marking a rare experiment in educating the children of impoverished families working the fields.

The camp’s school — then a 400-square-foot classroom carved out of the recreation room — was the first of its kind for migrant workers in New York State.

But that classroom was poorly maintained, wrote teacher Helen Prince, who worked at the camp for more than a decade.

In a detailed column printed by the Long Island Forum in 1989, Ms. Prince described a lack of school materials, a leaking sewer and an incident when a malfunctioning heater blew up in the classroom, covering her in soot.

She also said fights were common at the school, where students erupted into “rolling, fighting, pummeling groups” at the end of the school day. She later described how the president of the cooperative at the time responded to her complaints about the subpar conditions.

“But Helen,” he reportedly said. “You don’t have to teach them anything. You just have to keep order!” Still, Ms. Prince, who died last year, wrote that she did her best to provide an education for the children.

The school cycled through two other rooms before closing in 1962. Ms. Prince wrote that she often wondered about the “unfortunate children without hope for any kind of future.”

“One hauntingly beautiful young girl nags my Labor Camp memories,” she wrote. “She was quiet, totally withdrawn from her surroundings and rarely spoke. Maybe I should have sought to help her.”