How nitrogen finds its way into surface water

The Nature Conservancy released a report last week on the various ways nitrogen finds its way from the air and land and into surface waters throughout the Peconic Estuary.

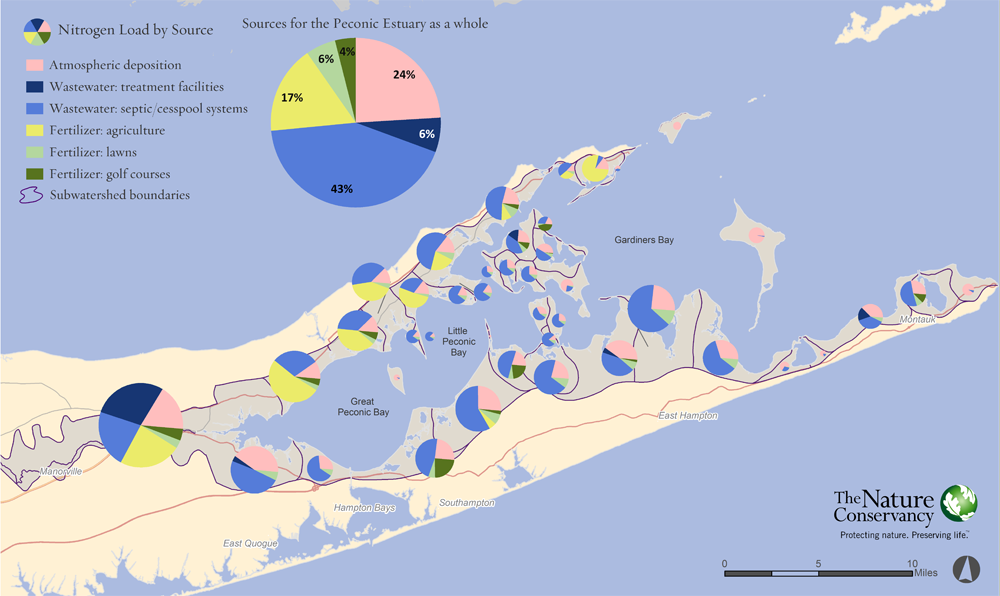

The report’s data shows that causes of nitrogen pollution vary significantly across the East End.

In many parts of the estuary, as suspected by researchers and environmental experts, septic systems were found to be the single largest single source of nitrogen, releasing 49.6 percent of the total amount entering Peconic waters. Other sources studied, referred to as “inputs,” included fertilizer from agriculture, lawns and golf courses, which accounted for 26.4 percent, and atmospheric deposits, which were found to contribute 24 percent, according to the overall figures.

- SEE FULL REPORT ON PAGE 2

But septic systems weren’t the leading source of nitrogen sources in all areas of the estuary.

The study identified agricultural fertilizer as the No. 1 source of nitrogen pollution in areas of the Great Peconic Bay and Little Peconic Bay on the North Fork’s southern shore, accounting for more than half the total there, as well as around Long Beach Bay in Orient, where it was found responsible for 77 percent.

“We see in the report that the North Fork is certainly the outlier when looking around the rest of Suffolk County,” said Christopher Clapp, a biologist with The Nature Conservancy, an international nonprofit environmental group with offices on the North Fork and elsewhere on Long Island.

In other parts of Suffolk County, the majority of the nitrogen is attributed to septic systems — with measurements of up to 70 percent, he explained, referring to countywide data.

“Along the North Fork and particularly the central part of the North Fork, because it is such an agricultural region, the nitrogen inputs from agriculture really do dominate the inputs,” he said.

Mr. Clapp said researchers “tried to be as fair as humanly possible to the agricultural community by including them in the process.”

Stephen Lloyd, a conservation information manager for The Nature Conservancy who authored the study, said he worked with representatives from Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County’s Agricultural Stewardship Program to better understand how agricultural land is being used across the North Fork.

Fertilizers are used differently on different types of crops, he explained.

“Vineyards, for instance, use very little fertilizer and won’t contribute much nitrogen at all,” Mr. Lloyd said.

By understanding how individual parcels of land are being used, study researchers could factor in different application rates and methods. Long Island Farm Bureau executive director Joe Gergela said the findings are generally consistent with what industry officials have been told in the past.

“We are aware of certain hot spots where water monitoring has shown high levels in micro-watershed areas,” he said. “In certain areas fertilizer will pass through.

“We admit it, we know it and were working on it,” Mr. Gergela said.

He said the study further emphasizes the need for assistance in funding research to help growers with integrating slow-release fertilizer and adopting other best-practice techniques.

“It’s not going to be fixed overnight. We need the funding and the help to address it,” he said. “Farmers are under a microscope.”

He added that, overall, the study confirms that “the main culprit is residential septic and sewage.”

According to the study, researchers used what is known as the Nitrogen Loading Model — which is widely used, in part because of its “ability to quantify sources of nitrogen with relative ease and accuracy, utilizing existing information about atmospheric deposition rates, on-site wastewater systems, sewage treatment plant outputs, fertilizer application rates, and spatial data on population, land use, and land.”

The same model has been used by the Environmental Protection Agency and by researchers on Cape Cod in Massachusetts, an area facing similar water quality issues, Mr. Lloyd said.

According to the study, atmospheric deposit rates were calculated from a Cedar Beach monitoring location in Southold belonging to the National Atmospheric Deposition Program.

It was the only available site within the study area, researchers said.

Mr. Gergela said in the future, he would like to see deposits from wildlife, including deer and Canada geese, accounted for in these studies.

High nitrogen levels in area waters have been feeding harmful algal blooms, which in turn have damaged the local ecosystem by depriving bodies of water of oxygen and negatively affecting area fisheries. Nitrogen levels have likewise been increasing in area drinking water.

“In deploying their nitrogen loading model, the Conservancy has specifically identified the sources of contamination from 43 areas in the Peconic Estuary,” Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone said last week in release about the study.

“It is this very specific scientific data that will provide a road map for Suffolk County as we set about reclaiming our waters,” he said.

In April, Mr. Bellone joined Congressman Tim Bishop (D-Southampton), county Legislator Al Krupski (D-Cutchogue) and a coalition of East End agricultural and environmental organizations to call on U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack to designate the Peconic Estuary as a critical conservation area under the Regional Conservation Partnership Program.

The designation would help to fund agricultural conservation and habitat restoration efforts within the estuary.

Water quality advocate Kevin McAllister said The Nature Conservancy report helps confirm the leading sources of nitrogen that need to be targeted in the future.

“A key point made here is that in implementing any kind of strategy or plan over time, we may have to address these watersheds individually, which may be the right prescription for improving things,” Mr. McAllister said.

The Nature Conservancy: Nitrogen Load Modeling to the Peconic Estuary by Timesreview